History

As the Temperance movement made headway, local options allowed localities to prohibit alcohol (“dry” counties). Franklin County remained “wet” and voted 1,373 against statewide prohibition with 1,079 for. However, the “drys” won the state, and under the Mapp Act, Virginia began statewide prohibition in 1916, three years before the 18th Amendment instituted national Prohibition. Ironically, Prohibition led to an increase in moonshining and to less money and fewer agents to enforce the regulations.

Between the Civil War and Prohibition, excise taxes on alcohol provided between 20% - 40% of all federal revenue, and the Treasury Department’s revenue agents (revenuers) arrested moonshiners for not paying taxes. Under Prohibition, there were no taxes on alcohol for personal consumption, and little funding for agents to enforce the Volstead Act laws concerning the manufacture, transportation, and sale of alcohol.

Pre-Prohibition, moonshining allowed small farmers to increase profits, and for many it was the one reliable source of cash. Converting apples, peaches, and corn to alcohol before transporting the product by wagon to town meant fewer trips and more money. Given the poor state of many roads and the reliance on wagons, a trip to town or a railroad station could take up an entire day. Multiple days spent hauling crops that could spoil could be reduced to one day hauling liquor that would not spoil.

Across the nation, farmers did not share in the economic prosperity of the early 1920’s. One Franklin county bootlegger stated in an interview with Essie W. Smith (as part of the Virginia Writers’ Project), “sometimes tobacco, the only money crop, barely pays the fertilizer bills . . . Sometimes [corn] brings such a small price it is not worth hauling it to market, but made up into whiskey there is always a good margin of profit”

In 1926, bootleg liquor sales reached an estimated $3.6 billion, approximately the size of the federal budget.

In 1929 alone, 35,200 illegal stills were seized in the U.S. During all of Prohibition, 3,909 stills were destroyed and 130,716 gallons of alcohol seized in Franklin County which accounted for 18% of the alcohol and 12% of the stills found by law enforcement in Virginia.

Franklin County went from 77 legal distilleries in 1893-1894 to 16 in 1906 to one in 1911 and none in 1917. Whiskey sold for $1.75 - $2.50 a gallon. During Prohibition, prices ranged from $6 to $12 to as much as $25 per gallon.

Before Prohibition took effect, many wealthy Americans, including politicians and business leaders who had voted or supported the dry position, began stockpiling enough liquor to last through their lifetimes. Locally, J. H. de-Hart of The Mountain Rose Distillery in Philpott, Virginia advertised reminding customers to submit orders that could be filled and delivered by October, 1916.

Many business leaders and politicians though it was acceptable for them to drink, but believed that excessive drinking was harmful to the working classes, so that Prohibition would be good for them by making alcohol unattainable. “When the working man spends eight hours at work and none in the saloon, he will save up more money and better his economic status . . . when [he] spends his evening at home or in the library . . . society will be better off” wrote William Allen White.

Even noted author and heavy drinker Jack London voted for women’s suffrage in 1911 because women would vote for Prohibition, which would make him stop drinking.

In fact, the Temperance Movement that led to Prohibition was supported by a diverse range of progressives and women’s rights advocates as well as religious conservatives in part because of the amount of excessive drinking and the resulting violence. Women and children did suffer both physical violence and poverty due to wages spent on alcohol and gambling instead of groceries and rent. In the early years of Prohibition, alcohol consumption did decline as did alcohol related illnesses, deaths, and crime, but as Prohibition continued, consumption, illness, and crime began to climb, with consumption reaching 70% of Pre-Prohibition levels. Some did stop drinking, but others drank even more. Ironically, drinking in public became socially acceptable for women in speakeasies and private clubs; whereas before, women would not enter a saloon, unless like Carrie Nation, it was to smash the liquor.

Even worse, crime and corruption increased. In 1920, for every one hundred thousand people, there were twelve murders. By 1933, this rate had increased to sixteen before beginning to drop after Prohibition ended, reaching ten by 1940.

Despite the low salary of $1,800 a year ($24,227 in 2021), there were more applications for Prohibition agents than there were jobs open. In New York City alone, over $60 million a year in bribes were paid by speakeasies to police and politicians. As U.S. Assistant Attorney General Mabel Willebrandt stated, if they aren’t taking the bribes, “they are either very honest or very stupid.” Law enforcement and political leaders at all levels, including the Assistant Secretary of the Treasury were involved in corruption and manufacturing or selling illegal alcohol, including politicians who had voted “dry.”

Small wonder that Franklin County farmers and business owners saw no need to stop making a product that was still in demand and even more profitable than before the 18th Amendment went into effect. They merely had to develop ways to evade or work with law enforcement.

Although there were some “very honest” law enforcement agents in Franklin County, others were less honest and certainly not “very stupid,” so it is not surprising that many moonshine stills were left alone by local deputies who received small bribes. There was no federal tax being evaded, so little incentive existed for federal agents to aggressively pursue moonshiners as they had before the 1920’s. Eventually, local Sheriff D. Wilson Hodges and others realized that they could profit from the moonshine trade by imitating the practices of big city rings. Thus in 1928, the “Moonshine Conspiracy,” which eventually gave Franklin County national notoriety in 1935, was born. Moonshiners had to leave bribes, known as a “granny fee” for law enforcement to prevent their stills from being smashed ($25 per still and $10 per whiskey load). As the fees increased, small time moonshiners were forced out of business and the illegal industry was consolidated. The same occurred on a national level.

However, the growth of moonshining in Franklin County was astounding. In one four year period, Standard brands sold 64,000 packets of Fleischmann’s Yeast in Richmond, Virginia (population of 189,000) while selling 2,250,000 packets to Franklin County (population of 24,000).

In addition, Franklin County imported over 115,000 pounds of copper and 700,000 five gallon metal cans during the same time.

Nationally, the production of corn sugar increased sixfold between 1919 and 1929. Most of that went to producing corn liquor.

Although the production of illegal whiskey and products used for both home brewing and distilling increased during Prohibition, “dry” and semi-dry politicians and civic leaders continued to support it. As a column in the New York World proclaimed:

“Prohibition is an awful flop.

We like it.

It can't stop what it's meant to stop.

We like it.

It's left a trail of graft and slime,

It's filled our land with vice and crime,

It don't prohibit worth a dime,

Nevertheless we're for it.”

Roots of Prohibition

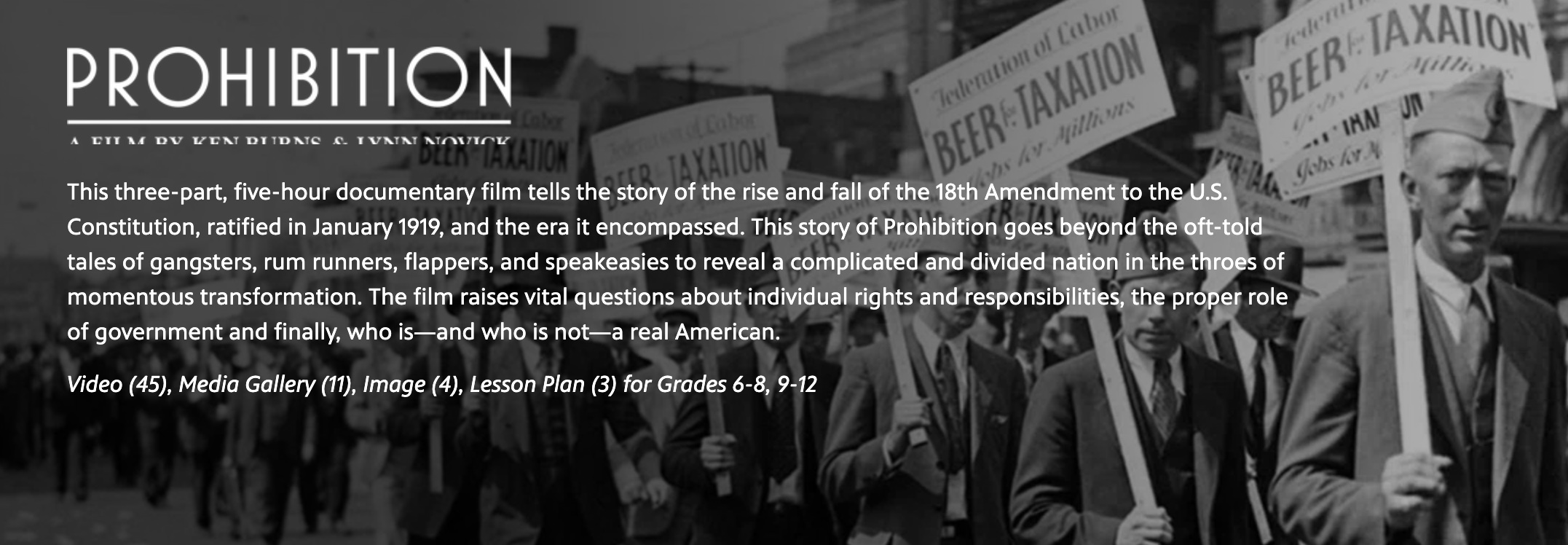

Watch the full Prohibition documentary.